When I get together with my old trekking friends the stories (and wine) flow and we are easily transported back to those heady days of mountains, remote trails and extraordinary people. The doors to old recollections open wide and we all remember things we thought we had forgotten.

Since my trekking days I have also done much by way of reading, lecturing and leading historical tours to the Himalaya and the great sub-continent. Enmeshed in all this are wonderful characters, exceptional events and periods in history and endless tales of magic and mystery.

Rather than storing all of this in my head, letting it loose only when people or events call for it I decided to write this blog, so that I can share some of it with like-minded souls who might appreciate a random tale or two from this extraordinary part of the world.

I hope you enjoy the occasional read. I will certainly enjoy the telling.

I had long admired Tenzing and his story from yak herder to one of the first two to summit Everest. When my chance came to meet him, I was beyond excited - yet also a little ill at ease. Perhaps he was not the man I had read about since childhood. Fame may have spoiled him. I had heard stories. Yet this was an opportunity not to be missed.

I was a working-class child from one of the less salubrious parts of Sydney. We didn't have many holidays, as I recall, but sometimes we would go up to the Blue Mountains and rent an old house in Blackheath for the winter vacation. I loved the cold and the brooding, misty mood of the mountains in winter. I did not know it then but mountains would become the spiritual backbone of my life – not simply those "blue" eucalypt-filled hills west of Sydney but those greatest of all mountains, the breathtaking, overwhelmingly beautiful peaks of the great Himalaya.

One year, when I was about ten, we stayed in an old place near Blackheath, whose décor could best be described as "early modern broken". It was very basic but it had a lovely garden, lined with tall emerald-green pines and criss-crossed with narrow paths between very old and little-tended rose gardens. And it had a large open fire facing two ancient armchairs – deep and welcoming. I was happy. I read everything I had with me and poked about for something else. On a small bookcase, blackened and smelling of soot from the fire, I found just two books – books that would, literally, change my life. One was Heinrich Harrer's "Seven Years in Tibet" and the other was "Man of Everest" – the autobiography of Tenzing Norgay as told to James Ramsey Ullman. I read Harrer first and was bewitched by this remote world beyond the Himalaya. Years later, in my twenties, when I stood on the small pass that led down into the great Yarlung-Tsangpo Valley of Tibet and looked across to the utter magnificence that is the great Potala Palace atop Marpori hill in Lhasa, I sat and wept openly, clearly remembering when I took that old book down from that shelf in the Blue Mountains. I am sure at that tender age, I did not actually know where the Himalaya was exactly but it appealed to the images in my head of some Shangri-La beyond wild and remote snowy peaks. The reality was all I could have hoped for – and utterly overwhelming.

Then I read Tenzing's book. And then I read it again. I was completely in awe of this man – a humble yak herder from a tiny valley east of Everest in Tibet, who dreamed of climbing the world's greatest peak – not for glory or to be "first" but because he simply wanted to climb it. It was connected to him spiritually – like a member of his family. I had never met a Sherpa – until then I do not think I had ever heard the term - but I knew that this man was unique, even among his own people. I sensed his drive, his willingness to take risks and his deep-rooted love for the Himalaya.

After my third reading, I decided to write to him. I had no idea of an address but figured that the Darjeeling Himalayan Mountaineering Institute would find him. I wrote that I knew little of him but that I was so utterly impressed by his humility and his quiet determination, by his view of Everest as a living, spiritual entity that must be respected and honoured. I walked into Blackheath, a long way and in howling, icy winds, bought a stamp and sent it on its way. I never received a reply. Tenzing was illiterate but I thought that maybe, just maybe, someone might write for him. But no. I then went about my life but read all I could about Everest, the old expeditions and the Sherpas. By the time I actually went to the Himalaya, at the age of 20, I was well-versed in mountaineering history and Sherpa ways.

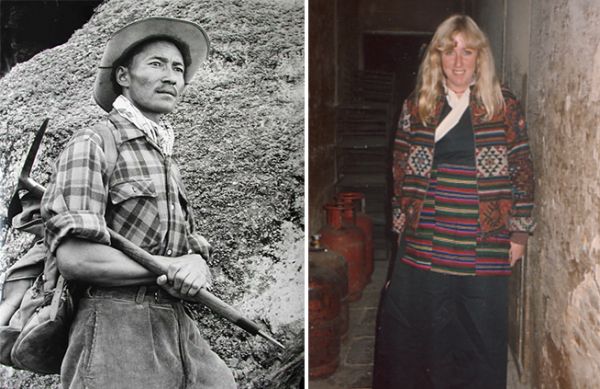

I gained work as a trekking and tour guide and, for a child who never walked anywhere – ever! – I grew to love the rhythm and peace of walking in the mountains. It nearly killed me at first but I watched the locals walk and found that their fast, light steps were far easier to manage than my slow, plodding gait. I learned a new way to move – and I learned to love it. I grew stronger, calmer and so very much happier. After several years I was asked by my trekking company to go to Darjeeling and meet with Tenzing Norgay, as he was our local agent for Darjeeling and Sikkim. I was beside myself. Star struck? Yes, absolutely. But more I was curious to compare the image I had built up in my head for all those youthful years with the reality. I had a bhaku, a traditional Sherpa dress, and I donned that for the short walk from my hotel to Ghang La, his rather grand post-Everest home in Darjeeling. On reaching the gate I was swamped by yapping, snapping Lhasa Apso pups – some harmless, some not. Then a heard a loud command in Tibetan and they all pulled back. At the top of the stairs stood Tenzing – Man of Everest – in his red down jacket and Swiss knickerbockers. That famous smile was all I needed to see that I would not be disappointed in the man I now met.

"Thuchey chey Tenzing la" – "thank you, Tenzing"

He was pleased that I had honoured his people by wearing my bhaku and he led the way into his sitting room. We sat and tea arrived – Tibetan tea, made with butter, salt and milk tea. An acquired taste but I had grown to love it after years in high, icy Sherpa villages. In very traditional Tibetan style it was served in porcelain cups sitting atop silver stands, engraved with mystical symbols and dragons - for good luck - and covered with ornate silver lids. Tenzing bowed as he stood and placed one before me – using both hands and with great respect. "Thuchey chey Tenzing la" – "thank you, Tenzing" – I replied.

I was on "cloud nine". We were meant to talk business but I had little interest. I wanted to talk Tenzing. I summoned up the courage to ask him if he had ever received a letter from a young child in Australia. He so kindly said that he did remember but I could see that he did not. I didn't mind. It led me on to explain how I came to know his story and he laughed. He said he had never read the book himself! I asked him about Nanda Devi, one of my favourite mountains – and about Charles Wylie, a British Gurkha officer and the only Everest 1953 team member who spoke Nepali and could truly communicate with him. Tenzing loved him and liked to talk about their friendship. I spent well over an hour in that house – looking at photos, awards and artefacts he had brought back from Tibet when he travelled there for almost a year with the Italian Orientalist scholar Dr Giuseppe Tucci. Wonderful things, magic names, mythical places. It was a day that remains deeply etched into my memory.

Business was eventually discussed and then, reluctantly, I had to leave. As I stood at the gate, yapping Apsos all around I received one more beaming smile from Tenzing. It was a morning I will never forget and one which flows back into my mind whenever I think of Everest and Tenzing. I had no way of knowing then but one day, many years later, I would look into the wide, dark eyes of my two children and see Tenzing's eyes. They are his great-grandchildren and are only now, in their twenties, beginning to realise the great honour and legacy that this humble Sherpa has left them. Thuchey chey, Tenzing-la.