When I get together with my old trekking friends the stories (and wine) flow and we are easily transported back to those heady days of mountains, remote trails and extraordinary people. The doors to old recollections open wide and we all remember things we thought we had forgotten.

Since my trekking days I have also done much by way of reading, lecturing and leading historical tours to the Himalaya and the great sub-continent. Enmeshed in all this are wonderful characters, exceptional events and periods in history and endless tales of magic and mystery.

Rather than storing all of this in my head, letting it loose only when people or events call for it I decided to write this blog, so that I can share some of it with like-minded souls who might appreciate a random tale or two from this extraordinary part of the world.

I hope you enjoy the occasional read. I will certainly enjoy the telling.

The history of the British in India is often romanticised and mythologised by historians and commentators yet it takes little effort to understand and acknowledge the absolute greed and opportunism with which the British, among other colonial powers of the time, pillaged and exploited the subcontinent – first in the name of trade, then in the name of empire and the civilising zeal of the Christian west. Yet, there can be no doubt that there were some – many – characters throughout Britain’s 250 years in India who intrigue and enchant readers and students of its history. Col. James Skinner was one such man. Here is his story.

Colonel James Skinner CB (1778 – 4 December 1841), often referred to as Sikandar Sahib later in life, was a maverick and a well-known Anglo-Indian military adventurer in India. He was instrumental in grooming two cavalry regiments for the British, later known as 1st Skinner's Horse and 3rd Skinner's Horse (formerly 2nd Skinner's Horse) at Hansi in 1803. His regiment is still part of the Indian Army.

James Skinner was born in 1778 in Calcutta (now Kolkata) to a Scottish father, Lieutenant-Colonel Hercules Skinner of the East India Company army and an Indian mother – a minor Rajput minor known only as Jeany - who had been taken prisoner by the British at age 14. James was one of fourteen children and, tragically, his mother committed suicide when he was 12.

Following her death, James and his brother Robert were sent to a charity school as their father could not afford to pay boarding-school fees for them. In 1794 however, the family's fortunes took a turn for the better when their father was promoted to Captain and the boys were promptly packed off to boarding school. Two years later James was bound for seven years as an apprentice to a printer. But the printing trade held little attraction for a boy whose ambition was to become a soldier or sailor. On the third night in his career as a printer he climbed over the walls of the house and absconded with four annas (eight pence) in his pocket. Within six days however, his money had run out and he found himself carrying loads or operating a carpenter's drill for two annas per day. But his career as an odd-jobman was cut short when he was discovered by a servant of his brother-in-law (Calcutta lawyer Thomas Templeton) who handed him over to Templeton. Templeton promptly put his errant brother-in-law to work copying legal documents, in return for his board. Here he stayed for three months before being 'rescued' in April 1796 by his godfather, Colonel Burn. Skinner's enthusiasm for his clerical career was as apparently as 'underwhelming' as his enthusiasm for his career as a printer, for when his godfather asked Templeton how Skinner was getting on he was assured by Templeton that the young man was 'a good-for-nothing fellow and not worth [his] salt.' Burn, after reprimanding Skinner for his idleness, asked the boy what he wanted to do and on being told by Skinner that he wanted to be a soldier or sailor, gave him 300 rupees and sent him to his father at Cawnpore. Fifteen days later Burn arrived in Cawnpore and gave Skinner a letter of introduction to Benoit De Boigne, a native of Savoy who was in the employ of Maratha chief, Mahadji Scindia, at Coel. Skinner arrived at Coel in early June and was given an ensign's appointment before being sent to the 2nd brigade at Muttra, where he was posted to a Nujeeb battalion under the command of Captain Pohlman. There can be little doubt that Skinner was suited to the military life, for he declared that 'perfecting myself in soldiering was my only pleasure

The Maratha Empire was a power that dominated a large portion of the Indian subcontinent in the 18th century. The empire formally existed from 1674 with the coronation of Shivaji and ended in 1818 with the defeat of Peshwa Bajirao II at the hands of the British East India Company. The Marathas are credited to a large extent for ending Mughal rule in India. James was taken on as an ensign under Benoît de Boigne, the French commander of Maratha Maharaja Sindia's forces of Gwalior State. Boigne was not only impressed by his talents but also that of his family ancestry. On his fraternal side, the Skinners had served William the Conqueror in the 11th century. Once taken in, Skinner soon showed shrewd military talent. He worked his way up to become commander-in-chief of Sindhia's army after Boigne's retirement, and remained in the post until 1803. He then lost the job after the second Anglo-Maratha War when all Angelo-Indian officers were dismissed from the military services.

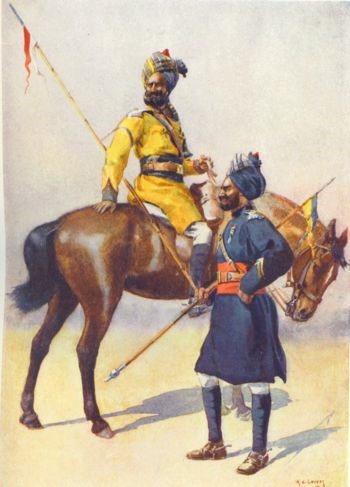

James Skinner -19th century - from Thomas Metcalfe's book dated 1843.

However, his military reputation and experience eventually enabled him to gain a place in the East India Company's Bengal Army – under Lord Blake, Commander-in-Chief of British Indian forces in 1801.

It was common practice at that time to recruit men for irregular forces from among prisoners of war. After the Battle of Delhi, when Lord Lake asked a group of such men whom they would have as their commander, the unanimous cry was 'Sikander Sahib' ~ that being the name by which James Skinner was known to Indian soldiers. This was the beginning of the famous force of irregular cavalry, which to this day (though now mechanised) is known as "Skinner's Horse". These redoubtable cavalrymen are also known to history as the 'Yellow Boys', named after their distinctive bright yellow uniform. A scion of Skinner, Brig Michael Skinner was in command of this unit of the Indian Army till his retirement and death some years ago.

Their mottos was the Persian Himmate Mardan, Madade Khuda (The courage of Man, with the help of God)

Skinner's Yellow Boys

After the siege of Bharatpur, in 1818 Skinner was granted a jagir (land grant) of Hansi (Hisar district, Haryana, south of Delhi), that fetched him an income revenue of Rs 20,000.00 a year, a staggering amount in those days.

In 1828 Skinner became a Lieutenant-Colonel in the British service and later became a colonel, after being awarded the Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB) on 26 December 1826.

After an illustrious military career James Skinner died in December 1841 at the age of 63. He was buried at Hansi with full military honours, his funeral cortege consisting of a long line of his beloved "Yellow Boys". The regiment continued after Skinner's death and in 1861 was renamed the 1st Bengal Cavalry as part of the post-Mutiny civil and military changes. Latterly it was re-classified as:

• the 1st Bengal Lancers in 1896

• 1st (The Duke of York's Own) Regiment of Bengal Lancers in 1899

• 1st (Duke of York's Own) Bengal Lancers (Skinner's Horse) in 1901

• 1st Duke of York's Own Lancers (Skinner's Horse) in 1903

• 1st Duke of York's Own Skinner's Horse in 1921.

The regiment remained in India during World War I, although the 3rd Skinner's Horse (with whom the 1st was amalgamated in 1922) was to serve in both France and the Middle East.

At the beginning of World War II the regiment was still mounted but was quickly converted to act as a mechanised reconnaissance regiment and was attached to the 5th Indian Division. The regiment fought in East Africa, North Africa and Italy and was awarded battle honours for Agordat, Keren, Amba-Alagi, Abyssinia, Senio Flood Bank and Italy.

The regiment was maintained by India upon independence and, like many British cavalry regiments became a tank regiment. Today the regiment still exists in the Indian army, fiercely proud of its long and glorious history.

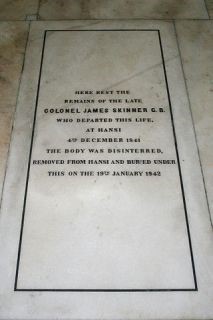

Although he was initially buried in the Cantonment Burial Ground at Hansi, 40 days after his death he was disinterred and his coffin brought to Delhi, escorted by 200 men of Skinner's Horse. He was buried in Skinner's Church on 19 January 1842 in a vault of white marble immediately below the Communion table. Here his soul is at rest in peace in the grave yard of the church that he had founded.

James Skinner's grave, St James Church, Delhi

St. James' Church or Skinner's Church, Delhi

The church was built between 1826-36 to a cruciform plan, with three porticoed porches and a central octagonal dome. It was consecrated on 21 November 1836 by the Right Reverend Daniel Wilson D.D, the Bishop of Calcutta

The story of this remarkable church, the oldest in Delhi, is no less romantic than that of its builder, James Skinner - a soldier, left dying on the battlefield, who vowed to build a church if his life were spared. Skinner not only survived to fulfill his vow but lived to see the day, November 21, 1836, when the noble monument of his piety and promise was consecrated and named after his patron saint.

It is worth mentioning the incident in his own words: "The Oonehara Rajah soon became aware of the badness of our troops and crossed the river on the 25th of January (1800)... Two of the enemy's battalions came up to attack me but I charged and drove them away." Later Skinner found that of his 300 men, only 10 were now with him. Skinner goes on to say, "As I was going to follow them (search for the other 290 men) a horseman galloped up, matchlock in hand, and shot me through the groin. It was about three in the afternoon that I fell, and I did not regain my senses till sunrise next morning... I crawled under a bush to shelter myself from the sun. Two more of my battalion crept near me ~ the one a soobahdar, that had his leg shot off below the knee, the other a jemindar had a spear wound through his body. We are now dying of thirst, but not a soul was to be seen; and in this state we remained the whole day, praying for death. Night came on but neither death nor assistance. The moon was full and clear and about midnight it was very cold. So dreadful did this night appear that I swore, if I survived, to have nothing more to do with soldering...the wounded on all sides, including his brother crying for water ~ the jackals tearing the dead and coming nearer and nearer to see if we were ready for them, we only kept them off by throwing stones and making noises. Thus, passed this long and horrible night (Hijr ki raat). Next morning we spied a man and an old woman, who came to us with a basket and a pot of water and to every wounded man she gave a piece of joaree (jowar) bread and drink from her water pot. But the soobahdar was a Rajpoot, he would receive neither bread nor water from her (as she was of a lower caste) so he preferred to die unpolluted." This was the woman whom the Colonel from then on regarded his mother...

Skinner – the man

As a result of his birth and of a career spent partly with the Marathas and partly with the British, Skinner moved between two worlds. His childhood memories of an Indian mother as well as his early years of fighting in central India, tied him to the Indian world. His domestic habits were more Indian than British and he had a large family by, it is said, 14 wives. His town house in Delhi was a fine mansion with high colonnades in the classical manner but with zenana quarters and Indian marble baths. At Hansi and Belaspore, in his country houses, he lived like an Indian landlord, taking a great interest in the cultivation of his estates. Many of his friends recalled the delicious Indian food, good conversation and relaxation with the hookah.

He spoke the local dialect fluently and to the end of his life wrote Persian more easily that English. He knew the name and village of origin of all his soldiers, inviting men of all ranks to his feasts.

Persian was the court and intellectual language of India in his day and he wrote several books in Persian, including "Kitab-i tasrih al-aqvam" (History of the Origin and Distinguishing Marks of the Different Castes of India), now with the Library of Congress. Other works included 'A folio of Tazkirat al-umara by James Skinner, 1830, depicting a Portrait of Maharaja Ranjit Singh of the Punjab. This included family biographies, of princely families in the Sikh and Rajput territories and 37 portraits of their current representatives. First translated from the original Persian by James Fraser and Skinner's Horse party Folio from 'Reminiscences of Imperial Delhi', an album by Sir Thomas Metcalfe, 1843.

A folio of Tazkirat al-umara by James Skinner, 1830, depicting Portrait of Maharaja Ranjit Singh of the Punjab.

It is said that James Skinner had fourteen wives and many children, one of whom was Mrs. Wagentreiber, who managed to escape the 1857 mutiny, due to the fact that he (Skinner) was greatly revered by the Indian Army regiments. His eldest son, also known as James Skinner, became an officer in Skinner's Horse and was killed in action during the First Anglo Afghan War. Many of his family members and their descendants are buried in Skinner's family plot, north of St. James' Church, Delhi.

There is mention of a grandson, also called James Skinner, who erected a statue of Queen Victoria upon her death, at his own expense at Chandni Chowk, Delhi. And in 1960, Lt-Col Michael Skinner, a great-great-grandson, took command of Skinner's Horse and was the first Skinner to command the regiment since its founder's death. In 2003, a special service was held at St. James' Church, Delhi to commemorate 200 years of Skinner's Horse, the cavalry regiment raised by Skinner in 1803, and amongst those present was Patricia Sedwards (née Skinner), niece of Lt-Col Michael Skinner.